In 1996, Henry Louis Gates, Jr., wrote about the life of Anatole Broyard, a literary critic who reinvented himself by denying his true identity.

In 1982, an investment banker named Richard Grand-Jean took a summer’s lease on an eighteenth-century farmhouse in Fairfield, Connecticut; its owner, Anatole Broyard, spent his summers in Martha’s Vineyard. The house was handsomely furnished with period antiques, and the surrounding acreage included a swimming pool and a pond. But the property had another attraction, too.

Broyard was born black and became white, and his story is compounded of equal parts pragmatism and principle. He knew that the world was filled with such snippets and scraps of paper, all conspiring to reduce him to an identity that other people had invented and he had no say in. Broyard responded with X-Acto knives and evasions, with distance and denials and half denials and cunning half-truths. Over the years, he became a virtuoso of ambiguity and equivocation.

Shirley has a photograph, taken when Anatole was around four or five, of a family visit back to New Orleans. In it you can see Edna and her two daughters, and you can make out Anatole, down the street, facing in the opposite direction. The configuration was, Shirley says, pretty representative. After graduating from Boys High School, in the late thirties, he enrolled in Brooklyn College. Already, he had a passion for modern culture—for European cinema and European literature.

He told his sister Lorraine that he had resolved to pass so that he could be a writer, rather than a Negro writer. His darker-skinned younger sister, Shirley, represented a possible snag, of course, but then he and Shirley had never been particularly close, and anyway she was busy with her own life and her own friends. They had drifted apart: it was just a matter of drifting farther apart.

The inauthentic Negro is not only estranged from whites—he is also estranged from his own group and from himself. Since his companions are a mirror in which he sees himself as ugly, he must reject them; and since his own self is mainly a tension between an accusation and a denial, he can hardly find it, much less live in it. . . . He is adrift without a role in a world predicated on roles.

In 1950, in a bar near Sheridan Square, Broyard met Anne Bernays, a Barnard junior and the daughter of Edward L. Bernays, who is considered the father of public relations. “There was this guy who was the handsomest man I have ever seen in my life, and I fell madly in love with him,” Bernays, who is best known for such novels as “Growing Up Rich” and “Professor Romeo,” recalls. “He was physically irresistible, and he had this dominating personality, and I guess I needed to be dominated.

One of those disputes was with Chandler Brossard, who had been a close friend: Broyard was the best man at Brossard’s wedding. There was a falling out, and Brossard produced an unflattering portrait of Broyard as the hustler and opportunist Henry Porter in his 1952 novel, “Who Walk in Darkness.” Brossard knew just where Broyard was most vulnerable, and he pushed hard. His novel originally began, “People said Henry Porter was a Negro,” and the version published in France still does.

Someone both Porter and I knew quite well once told me the next time he saw Porter he was going to ask him if he was or was not an illegitimate. He said it was the only way to clear the air. Maybe so. But I said I would not think of doing it. . . . I felt that if Porter ever wanted the stories about himself cleared up, publicly, he would one day do so. I was willing to wait.

Anne Bernays maintains, “If you leave the sex part out, you’re only telling half the story. With women, he was just like an alcoholic with booze.” She stopped seeing him in 1952, at her therapist’s urging. “It was like going cold turkey off a drug,” she says, remembering how crushing the experience was, and she adds, “I think most women have an Anatole in their lives.”

It’s an image of self-assemblage which is very much in keeping with Broyard’s own accounts of himself. Starting in 1946, and continuing at intervals for the rest of his life, he underwent analysis. Yet the word “analysis” is misleading: what he wanted was to be refashioned—or, as he told his first analyst, to be. “When I came out with the word, I was like someone who sneezes into a handkerchief and finds it full of blood,” he wrote in the 1993 memoir.

In 1963, just before their first child, Todd, was born, Anatole shocked his friends by another big move—to Connecticut. Not only was he moving to Connecticut but he was going to be commuting to work: for the first time in his life, he would be a company man. “I think one of his claims to fame was that he hadn’t had an office job—somehow, he’d escaped that,” Sandy says. “There had been no real need for him to grow up.

Even in Arcadia, however, there could be no relaxation of vigilance: in his most intimate relationships, there were guardrails. Broyard once wrote that Michael Miller was one of the people he liked best in the world, and Miller is candid about Broyard’s profound influence on him. Today, Miller is a psychotherapist, based in Cambridge, and the author, most recently, of “Intimate Terrorism.” From the time they met until his death, Broyard read to him the first draft of almost every piece he wrote.

It is unfortunate that the author of “A Shadow on Summer” is an almost total spastic—he is said to have typed his highly regarded first novel, “Down All the Days,” with his left foot—but I don’t see how the badness of his second novel can be blamed on that. Any man who can learn to type with his left foot can learn to write better than he has here.

Nor did relations between the two daily reviewers ever become altogether cordial. Lehmann-Haupt tells of a time in 1974 when Broyard said that he was sick and couldn’t deliver a review. Lehmann-Haupt had to write an extra review in less than a day, so that he could get to the Ali-Frazier fight the next night, where he had ringside seats.

Some people speculated that the reason Broyard couldn’t write his novel was that he was living it—that race loomed larger in his life because it was unacknowledged, that he couldn’t put it behind him because he had put it beneath him. If he had been a different sort of writer, it might not have mattered so much. But Merkin points out, “Anatole’s subject, even in fiction, was essentially himself. I think that ultimately he would have had to deal with more than he wanted to deal with.

Sandy speaks of these matters in calmly analytic tones; perhaps because she is a therapist, her love is tempered by an almost professional dispassion.

Every once in a while, however, Broyard’s irony would slacken, and he would speak of the thing with an unaccustomed and halting forthrightness. Toynton says that after they’d known each other for several years he told her there was a “C” on his birth certificate. “And then another time he told me that his sister was black and that she was married to a black man.” The circumlocutions are striking: not thatwas black but that his family was.

All the same, Schwamm was impressed by a paradox: the man wanted to be appreciated not for being black but for being a writer, even though his pretending not to be black was stopping him from writing. It was one of the very few ironies that Broyard, the master ironist, was ill equipped to appreciate.

Gradually, a measure of discontent with Broyard’s reviews began to make itself felt among the paper’s cultural commissars. Harvey Shapiro, the editor of thefrom 1975 to 1983, recalls conversations with Rosenthal in which “he would tell me that all his friends hated Anatole’s essays, and I would tell him that all my friends loved Anatole’s essays, and that would be the end of the conversation.” In 1984, Broyard was removed from the dailyfrom 1983 to 1989, edited Broyard’s column himself.

The act of razoring out your contributor’s note may be quixotic, but it is not mad. The mistake is to assume that birth certificates and biographical sketches and all the other documents generated by the modern bureaucratic state reveal an anterior truth—that they are merely signs of an independently existing identity. But in fact they constitute it.

Sandy says that they had another the-children-must-be-told conversation shortly before the move. “We were driving to Michael’s fiftieth-birthday party—I used to plan to bring up the subject in a place where he couldn’t walk out. I brought it up then because at that point our son was out of college and our daughter had just graduated, and my feeling was that they just absolutely needed to know, as adults.” She pauses. “And we had words. He would just bring down this gate.

It pains Sandy even now that the children never had the chance to have an open discussion with their father. In the event, she felt that they needed to know before he died, and, for the first time, she took it upon herself to declare what her husband could not. It was an early afternoon, ten days before his death, when she sat down with her two children on a patch of grass across the street from the institute.

The writer Leslie Garis, a friend of the Broyards’ from Connecticut, was in Broyard’s room during the last weekend of September, 1990, and recorded much of what he said on his last day of something like sentience. He weighed perhaps seventy pounds, she guessed, and she describes his jaundice-clouded eyes as having the permanently startled look born of emaciation. He was partly lucid, mostly not. There are glimpses of his usual wit, but in a mode more aleatoric than logical.

France Dernières Nouvelles, France Actualités

Similar News:Vous pouvez également lire des articles d'actualité similaires à celui-ci que nous avons collectés auprès d'autres sources d'information.

David Yurman taps Henry Golding, Scarlett Johansson for emotive filmsU.S. jeweler David Yurman is encouraging authentic connections in its first ambassador-led campaign.

David Yurman taps Henry Golding, Scarlett Johansson for emotive filmsU.S. jeweler David Yurman is encouraging authentic connections in its first ambassador-led campaign.

Lire la suite »

Henry Ruggs Crash Victim Tina Tintor Honored With Mural Near Wreck SiteTina Tintor and her dog have been memorialized with a mural in Las Vegas ... three months after they tragically died there in a car crash involving former NFL star Henry Ruggs.

Henry Ruggs Crash Victim Tina Tintor Honored With Mural Near Wreck SiteTina Tintor and her dog have been memorialized with a mural in Las Vegas ... three months after they tragically died there in a car crash involving former NFL star Henry Ruggs.

Lire la suite »

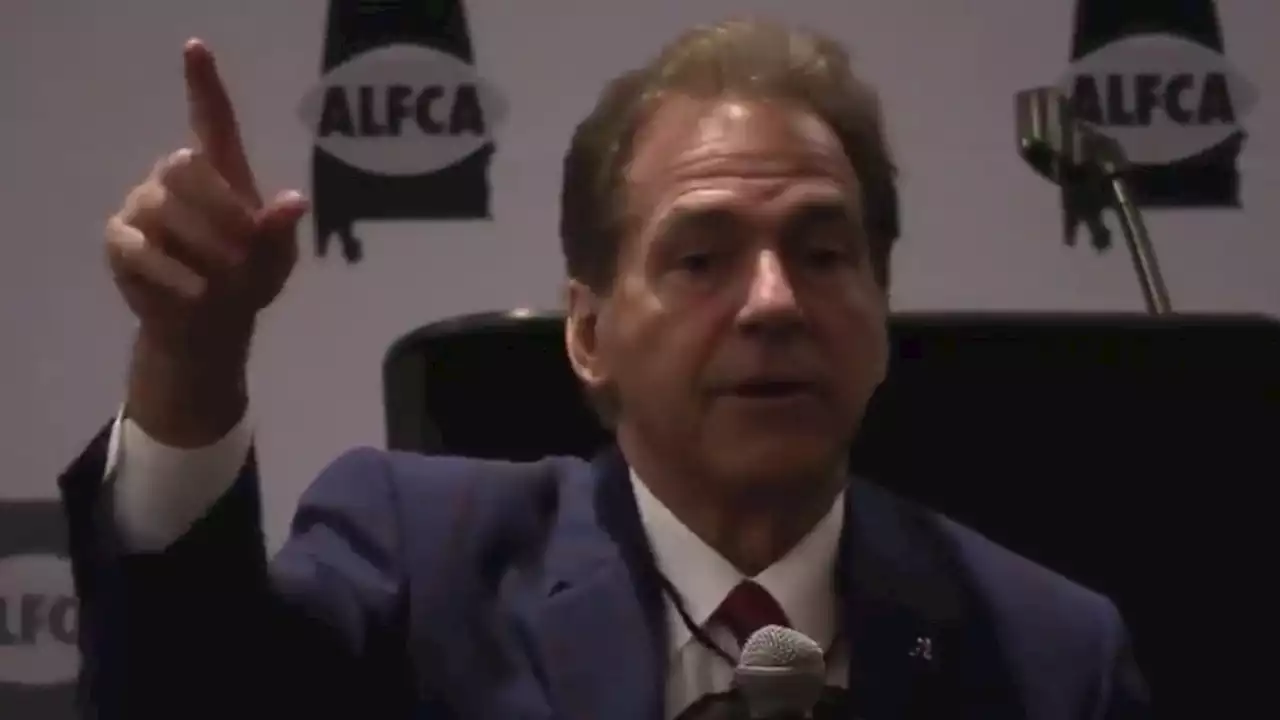

Nick Saban Says Friends Could Have Stopped Henry Ruggs CrashNick Saban brought up former Alabama star Henry Ruggs' accident in an emotional speech about leadership.

Nick Saban Says Friends Could Have Stopped Henry Ruggs CrashNick Saban brought up former Alabama star Henry Ruggs' accident in an emotional speech about leadership.

Lire la suite »

3 top-ranked dividend stocks for February yielding as high as 8.6%Morgan Stanley really likes these companies with a track record of raising dividends

3 top-ranked dividend stocks for February yielding as high as 8.6%Morgan Stanley really likes these companies with a track record of raising dividends

Lire la suite »

Psaki won’t comment on Clinton-linked tech exec ‘mining’ WH recordsWhite House press secretary Jen Psaki declined to comment Wednesday on special counsel John Durham’s allegation that tech executive Rodney Joffe mined “non-public” White House int…

Psaki won’t comment on Clinton-linked tech exec ‘mining’ WH recordsWhite House press secretary Jen Psaki declined to comment Wednesday on special counsel John Durham’s allegation that tech executive Rodney Joffe mined “non-public” White House int…

Lire la suite »

Shaun White Jokes of Comeback, Talks Retirement Plans on 'TODAY'🏂 Snowboarding legend ShaunWhite joked of a comeback while talking about his retirement plans on the TODAYShow.

Shaun White Jokes of Comeback, Talks Retirement Plans on 'TODAY'🏂 Snowboarding legend ShaunWhite joked of a comeback while talking about his retirement plans on the TODAYShow.

Lire la suite »